Ways to Include Student Voice in Your Teaching

December 5, 2017

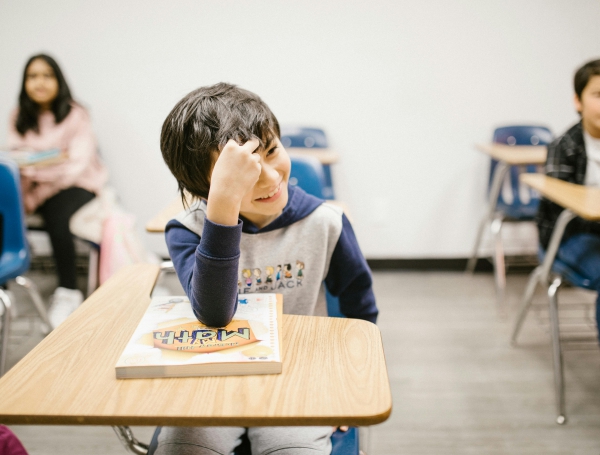

Some of the most impactful learning comes from activities that allow students to speak their minds and volunteer their own opinions. As a history teacher, I have found (through trial and error), that students are usually only engaged when they feel content is relevant to their lives--at least at the high school level. One of the ways that I try to make my content feel more relevant to my students is by giving them multiple opportunities to connect their own thoughts to the topics we cover in class. Not only does this increase engagement, it also helps students build the critical thinking skills required to see connections between events and to understand the value of learning about historical phenomena. And involving student voice in your class can apply to any subject matter: science, English, history, and math.

There are a lot of ways to include student voice in your teaching practice. It can be as simple as asking students to offer their opinions on a topic covered in direct instruction. I often fall back on think-pair-share, when you pose a question to students, let them think about their answers individually, have them share their answers with a partner, and then ask them to share out with the whole class. Think-pair-share helps students feel like they’re accountable for the material being discussed, gives them a safety net (partner share) that they don’t have when they get called on, and it provides an easy formative assessment to see whether or not students have understood your lesson.

Another strategy I employ frequently is the seminar format, sometimes called a “Socratic seminar.” The “Socratic” seminar gets its name from the Greek philosopher Socrates, who was famed for his unique style of questioning his students in order to create deeper thinking. In a high school classroom, I find Socratic seminars to work best when you want students to consider the moral implications of an issue, or when you want them to explore multiple sides of a potentially controversial subject. Seminars require students to speak up in front of their peers (and they require all students to speak), to defend their opinions with evidence, and to construct thoughtful, probing questions to ask their peers. Because of this list of tasks, seminars require students to demonstrate a wide range of skills and to be relatively solid in their content knowledge. Seminars allow students to direct the flow of the conversation in class, and I often come away from student seminars having heard an idea or connection I hadn’t made on my own. More often than not, students leave the room still talking about the issue they had been discussing in the seminar.

Increasing student voice in the classroom is a great way to improve student engagement. Since I made the move to focus specifically on student voice in my classroom, rigor has increased and so has student participation. The more you ask students for their input and opinions, the more valued they will feel in your class, and the more they’ll want to attend and strive to be their best.

Article by Alison McCartan, a regular contributor to The Heritage Institute's Blog, What Works: Teaching at Its Best.

Article by Alison McCartan, a regular contributor to The Heritage Institute's Blog, What Works: Teaching at Its Best.

Alison McCartan is a high school teacher in the South Puget Sound region of Washington State. She has taught English and history in high schools across the country, and when she's not orchestrating re-enactments of the Industrial Revolution in class, she can usually be found with a cup of tea, her cat, and a book.