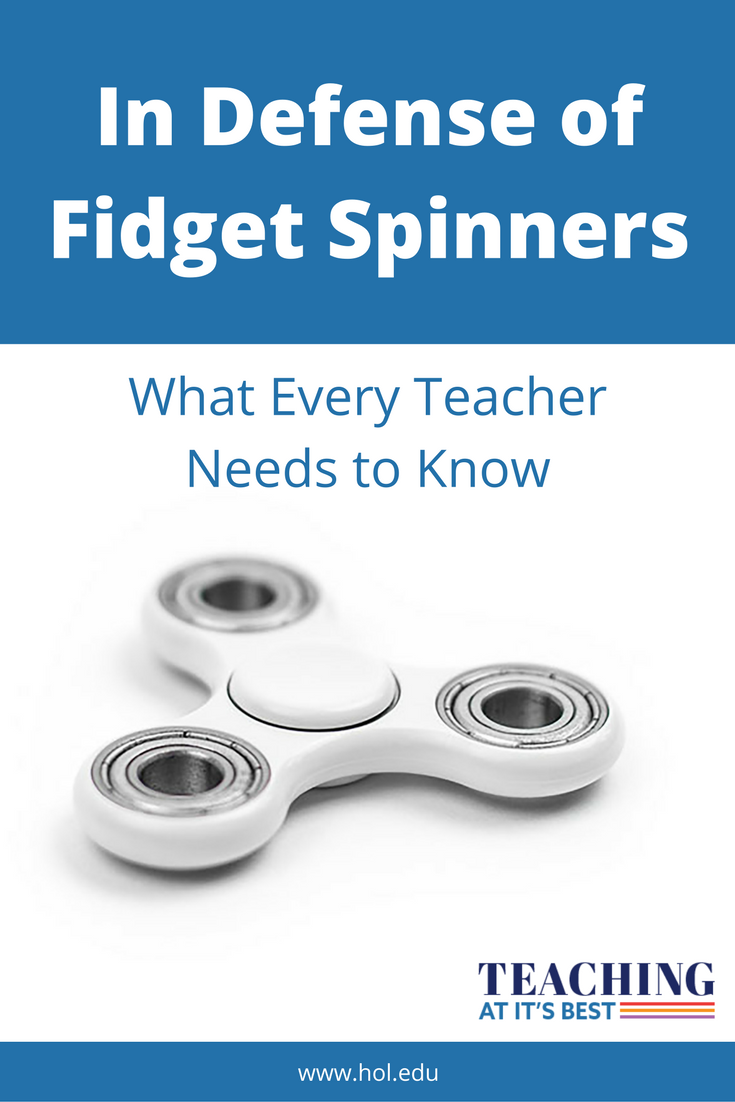

In Defense of Fidget Spinners

July 13, 2017

If you work in a school, you probably know what a fidget spinner is. You may have even seen other types of fidget toys in the hands of your students: fidget cubes, fidget dice, sensory and tactile toys, and more. Originally designed and marketed as a toy to help learners with attention challenges, these handheld toys have taken off in popularity in the last few months. In my high school classroom alone, we went from one to what seems like one for everyone in a matter of weeks.

As their popularity has grown, so has the controversy surrounding the use of fidget toys in the classroom. Teachers, educators, and parents have voiced concerns about the potential for distraction, and debates about their merits are circulating across news articles and blog posts. But if you work in a classroom, fidgets are probably part of your daily routine now, whether you like them or not. And while they present real management concerns, I can say that in six years of teaching, no tool so simple has helped me so much in managing distracted, off-task, and disruptive students.

It took me somewhat by surprise. I was first introduced to fidget spinners (and fidget toys) when a student of mine brought one into class, explaining that his mom had gotten it to help him with his ADHD symptoms. His first day with it, I was impressed: he was more focused, completed more work in class, stayed in his seat longer, and did not once pull out his cellphone. Curious about what they could do for my other students, I went out and bought an assortment of fidget toys, and the next time I delivered a lesson, I quietly passed them out to the most distractible students in my class.

The change was dramatic--and positive. One student, a bright, curious, energetic young man, came into the last class of the day full of energy and spent the first fifteen minutes of class actually bouncing in his seat. He was completely disengaged in the lesson, talking to his neighbors, playing with his hair, and turned away from the board. Five minutes after giving him a fidget toy, he’d settled into his seat, turned around, started taking notes on the lesson, and raised his hand to ask an on-topic question. Another student who had struggled the entire year to write more than one sentence at a time without constant coaching, took a fidget toy from me and wrote an entire essay paragraph in fifteen minutes, without one prompt or redirect from me.

These two cases alone would have been enough to convince me, but it hasn’t been just these two students. Many students who are never disruptive and seem rarely off-task ask for the toys, citing days when they used them experimentally and were surprised by how much they got done. They work as rewards for students who need an incentive, and they’re a really good substitute for cellphone games.

I don’t want to minimize the concerns that exist around fidget toys. As many other educators have expressed, they bring many opportunities for additional distraction along with the potential help they offer. Through the course of this experiment, I have learned where boundaries need to be established around their use and how to predict which students will use them responsibly. I’ve explained new rules about fidget toys to my students as the need rises, and explained my goals in using them so that my students understand that our ultimate goal is always to make sure they are able to succeed at the best of their abilities.

Despite the challenges they present, the benefits I have witnessed make fidget toys a classroom tool that any teacher should consider. Now that we as an educational community have recognized that students who lose instructional time due to discipline often struggle in school long-term, we need to seek out creative and positive solutions for day-to-day classroom misbehaviors. Fidget toys are one simple, easy way to keep kids in class and make sure the focus of every class is learning.

Article by Alison McCartan, regular contributor to The Heritage Institute's Blog, What Works: Teaching at Its Best.

Article by Alison McCartan, regular contributor to The Heritage Institute's Blog, What Works: Teaching at Its Best.

Alison McCartan is a high school teacher in the South Puget Sound region of Washington State. She has taught English and history in high schools across the country, and when she's not orchestrating re-enactments of the Industrial Revolution in class, she can usually be found with a cup of tea, her cat, and a book.